Two local photographers who combined art and activism to preserve Laguna’s critical natural corridor are celebrated in a new book and museum exhibition.

By Richard Chang

As you follow state Route 133 toward the coast, the land opens up. Behold Laguna Canyon, where miles of undeveloped property lie untouched, as they have for hundreds of thousands of years. The area is one of the last pristine, untarnished passages from the hills to the sea in all of Southern California.

But it wouldn’t be preserved the way we know it now, had it not been for two determined locals who inspired the battle for its conservation. In the 1980s, Jerry Burchfield and Mark Chamberlain, photographers and friends who opened BC Space Gallery on Forest Avenue, saw a specter of development in the canyon and wanted to stop it in its tracks. It was at BC Space that the Laguna Canyon Project—a unique blend of art and activism, or “artivism”—was born: Over the course of 30 years, the pair used photography to draw attention to the importance of the canyon as part of the identity of Laguna Beach.

Now, their efforts are being highlighted in “Laguna Canyon Project: Defining Artivism,” a book due to be published within the next year by Laguna Wilderness Press. This fall, Laguna Art Museum also pays homage with “The Canyon Project: Artivism” (Oct. 18 to Jan. 17, 2016), an exhibition featuring photography, assemblage, documents and ephemera related to various phases of the project.

In the Beginning

“We started talking about it in 1975,” Mark recalls. “The Canyon Project was a product of many darkroom conversations between Jerry and I, and what we might be able to do to protect Laguna from obvious development plans. We saw that they wanted to build a city out of the canyon. We were terrified about what was likely to happen if something wasn’t done.”

Mark, whose early days in Laguna Beach included the famed Christmas Happening concert in 1970 in the canyon, can point to plenty of other examples of rapid development from Orange County’s inland to the coast. Consider, for instance, Crown Valley Parkway in nearby Laguna Niguel and Mission Viejo.

“If the canyon turned into Crown Valley Parkway, Laguna would be consumed by that as well,” he says. “The canyon is crucial to the identity of Laguna Beach.”

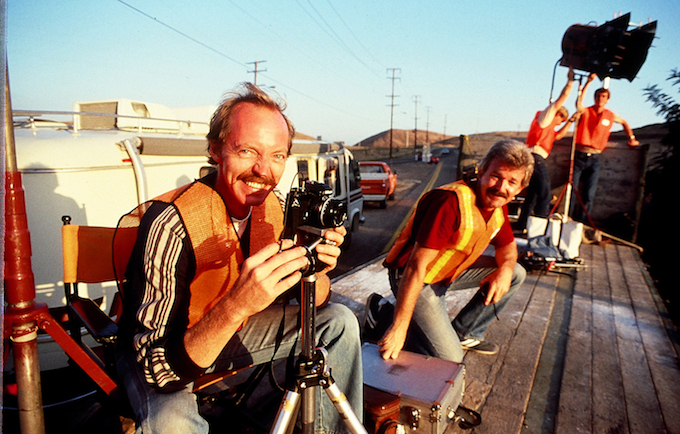

After many discussions, the two photographers did what they knew best. Starting in 1980, they shot Laguna Canyon Road with their cameras, foot by foot, inch by inch. In thousands of separate frames, they documented the stretch from the Santa Ana Freeway (Interstate 5) to the Pacific Ocean, or what Mark calls “the last 9 miles of the westward migration.”

“When I got to town, and Jerry as well, it was still country,” Mark says. “It was agricultural, and cows grazed on the side. We kind of declared to the world that we saved Laguna Canyon on film. Will the populace rise to the occasion and save it in reality?”

In subsequent phases—aided by a handful of other artists and activists—the pair continued to document Laguna Canyon Road at the beginning of each decade. In addition to rolls and rolls of daytime scenes, they developed hundreds of nighttime photos. They also took a crew out at night and “painted the canyon” with red, green and blue light, and captured that on film.

But what started as photographic documentation grew into an ever-evolving work of performance art that would attract nationwide attention—just nine years after the initial phase, Jerry and Mark would take their “artivism” to the next level in light of impending developments in the canyon.

Telling the Masses

In 1989, plans were rolling to start construction on Southern California’s first toll road. Blueprints were also drawn for the approximately 3,200-unit Laguna Laurel housing project, to be built by the Irvine Co. in Laguna Canyon, in addition to other commercial developments and a golf course.

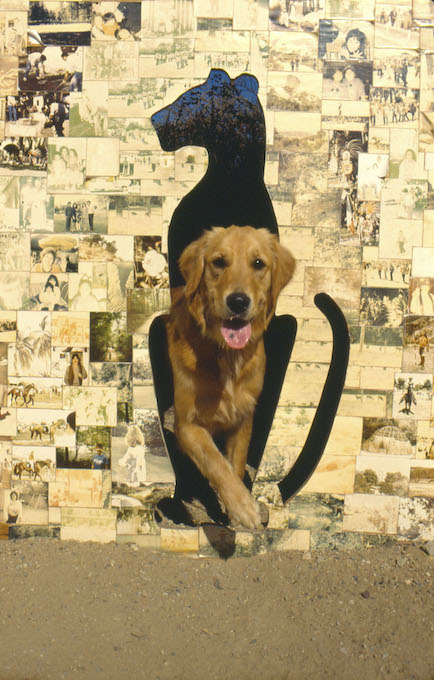

Observing all the commotion, the organizers of the Laguna Canyon Project felt compelled to action. That year, Jerry, Mark and a growing crew of volunteers constructed a large outdoor mural supported by an extensive wooden frame, stretching nearly 5 miles into the canyon across from the proposed housing project. The curves and undulations echoed those of its surrounding environment, and an Easter Island head served as a focus and foundation. The decorations would be photographs—hundred of thousands of them, to be contributed by locals, passersby, whoever wanted to add to the collection.

The mural evolved into “The Tell,” a collaborative photographic piece that reflected concerns about the preservation of Laguna Canyon, and the everyday lives of its contributors. At its height, “The Tell,” which borrowed its name from an archaeological term for a mound of artifacts left over from previous civilizations and buried by natural elements, stretched 636 feet long and more than 30 feet high. It was covered with about 100,000 photographs of people, places, pets, homes and trips, donated by people from across the country.

Local and national media outlets closely covered the building of the photomural. In a Los Angeles Times piece published in August 1989, Cathy Curtis called it a “peculiarly modern kind of folk art—quilting bee, barn-raising and hell-raising all in one.” She concluded, “It’s a town meeting disguised as a work of art.”

“I was really impressed,” says Mike McGee, who visited “The Tell” in its heyday. Mike, a California State University, Fullerton art professor and director of the college’s Begovich Gallery, is curating the Laguna Art Museum exhibition about the project.

“That element of getting the public involved and mobilizing the public was such an amazingly successful part of that project,” Mike adds. “ ‘The Tell’—that really was the phase that had an impact.”

On Nov. 11, 1989, roughly 8,000 people walked from downtown Laguna Beach to the site of the photomural in the march to save Laguna Canyon. At “The Tell,” participants demonstrated against the proposed Laguna Laurel housing project and other developments planned for the area.

“It mobilized people,” Mike recalls. “It got so many people out there. People who didn’t know what BC Space was. Artists from all over Orange County were there.”

The protests and media coverage caught the attention of the Irvine Co., which eventually agreed to release the land to the city of Laguna Beach. In 1990, residents voted to tax themselves to help pay for the purchase of the land and keep it as preserved, open space.

A Legacy of Artivism

Many more phases of the Laguna Canyon Project followed, with the final documentation completed June 21, 2010, in memory of Jerry, who had cancer and died in September 2009. (Update: Mark later died in 2018.) But the legacy of the project, and its extraordinary blend of art and activism, lives on.

“You can absolutely say with some certainty that if that project hadn’t happened, [Laguna Laurel] would have gone ahead,” Mike says. The project “preserved a corridor that went all the way to the Cleveland National Forest, and indigenous animals travel along that corridor. If you disrupted that, it could have had an even more negative impact.”

“The Tell” didn’t stand for long—it was disassembled in 1990—but the new Laguna Art Museum exhibition gives visitors the opportunity to get an idea of what it felt like to contribute to such an effort. Curator Mike says he aims to reconstruct the tale of “The Tell” with a computer program that will project images sent from participants onto a scaled replica of the photomural.

“As an exhibition about artists taking action to help preserve the natural environment, it fits perfectly with the museum’s annual Art & Nature festival, which this year takes place Nov. 5-8,” says Malcolm Warner, executive director of Laguna Art Museum. “The idea is to document the Laguna Canyon Project as part of the history of our community rather than to draw attention to any issue of the present. But certainly it’s a model of how art can serve a cause. Young artists will see how energized [Jerry] Burchfield and [Mark] Chamberlain were and may well feel challenged to get involved in causes of their own.”

Art Meets Altruism

In addition to environmental activism, art is combined with philanthropic causes in organizations throughout Laguna Beach, from the art festivals to nonprofit groups and City Hall. Here are just a few local efforts that are making a difference now.

Festival of Arts Foundation

Started in 1989, the Festival of Arts Foundation provides grants to various Laguna Beach nonprofits, especially those combining education, young people and the arts. The foundation and the Festival of Arts have cumulatively awarded nearly $2.6 million in grants to the local art community and more than $3 million in scholarships.

“We want to make sure art and art instruction are available in the schools, from kindergarten through high school,” says foundation President Scott Moore. “We are being as active as we can to put that in front of them.” Applications are typically due in February.

Artists’ Benevolence Fund

Sawdust Art Festival operates multiple year-round programs that assist the less fortunate. The Artists’ Benevolence Fund can be traced back to 1987, when artwork was auctioned off to help a critically ill Sawdust Art Festival artist. Today it provides financial assistance to artists living in Laguna Beach who have suffered a catastrophic event, making them unable to work. The Artists’ Benevolence Fund annual art auction fundraiser typically takes place in August.

Art Enrichment Fund

Sawdust Art Festival is also behind the Art Enrichment Fund, which supports public art education through hands-on experiences creating one-of-a-kind pieces. The programs frequently utilize Sawdust artists who provide art instruction for at-risk youth, armed forces personnel and their families, individuals going through therapy and homeless people discharged from local hospitals.

Laguna Outreach for Community Arts

Laguna Outreach for Community Arts (LOCA) offers numerous programs and classes in and around Laguna Beach. LOCA’s Art Escapes are popular, affordable workshops for seniors. LOCA also collaborates with other local organizations; for example, it works with the Woman’s Club of Laguna Beach on the Intergenerational Literacy Enhancement Project, which helps third graders with reading comprehension.

Photos by BC Space

On the 2015 article: This town is a unique intersection of artists and politically active residents who are passionate about issues like conservation. The Tell is the epitome of those two elements coming together to save the very fiber of this town’s character.