The reincarnation of a bluff top in Laguna honors California’s coastal beauty and the surrounding community.

By Marina Chetner | Photos by Jody Tiongco

Treasure Island Park may very well be a microcosm of Laguna Beach. It’s eclectic, artful and devastatingly beautiful; at every turn, pink bougainvillea, purple pride of Madeira and birds of paradise perfectly frame craggy cliffs and the glorious swells of the Pacific Ocean. Part and parcel of the Montage Laguna Beach property, the park and its adjoining beaches has stood open to the public for more than a decade. The site’s swanlike metamorphosis is a testament to the success of the collaborative relationship between the city, developer, community groups and a not-so-shy public; it created not only a prized public space but also a model that continues to be lauded by developers today.

But the process wasn’t without its challenges; after all, transforming an asphalt-laden space into a functional park and botanical garden required careful consideration. “Everyone was working hard to figure out the character of this place so that we were all playing off the same sheet of music,” says William Burton, landscape architect and president of the Solana Beach, Calif.-based Burton Landscape Architecture Studio, one of the firms that contributed to the space’s redesign. The development of the site, a prime parcel of oceanfront property in south Laguna, has led to the revitalization of one of the area’s most beloved pieces of land.

Site of History

Laguna’s artistic charm traces back to the early 1900s and the arrival of artist Norman St. Clair, who influenced the growth of the plein-air art movement on the West Coast. At the same time, parts of Laguna, including the eventual park site,  were homesteaded, farmed and planted with groves of eucalyptus “timber.” The construction of Pacific Coast Highway in the late 1920s and a change in land ownership led to the development of the Treasure Island mobile home park; its name inspired by the 1934 cinematic adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel of the same name.

were homesteaded, farmed and planted with groves of eucalyptus “timber.” The construction of Pacific Coast Highway in the late 1920s and a change in land ownership led to the development of the Treasure Island mobile home park; its name inspired by the 1934 cinematic adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel of the same name.

“In 1939, the trailer park expanded from 30 to 200 trailers,” says Jane Janz, a board member of the Laguna Beach Historical Society. “One hundred more sites were added in 1946 and, by 1947, up to 6,000 touring trailers would stop at Treasure Island.” Unfortunately, the gated community locked out a beach-seeking public.

After a group called Treasure Island Associates acquired the land in 1989, the defeat of a local rent control referendum and city rezoning led to the 60-year-old mobile home park’s closure, and it was officially cleared of residents by 1997. A broad-strokes plan to redevelop the land with a hotel and residences (a financially viable option given bed and property tax revenues), a bluff-top park and public beach access was well received by the city and attracted the attention of an experienced developer, the Athens Group.

Some locals, however, argued that the residential and hotel components were too dense and commercial for close-knit Laguna, which was then home to just over 24,000 people; others, meanwhile, felt that the site should be used as parkland. The fate of an amended plan was decided by an April 1999 referendum vote, which revealed a 55 percent majority in favor of the project.

“The project was unanimously approved by the California Coastal Commission (CCC) because of its visitor-serving value to a spectacular coastal site with beach access,” says Susan Whitin, president of the Laguna-based firm Whitin Design Works, which consulted on the landscape concept of the master plan. “Before the Montage was built, there was no public access, and the fence along PCH walled off views and access to the beach.” The CCC’s ringing endorsement, meant to open up the land to the public, pushed development forward.

By Design

Burton Landscape Architecture Studio joined the project in late 1999 to help manifest the vision for the site’s design. “We looked at the project with a fresh set of eyes,” William says, adding that he attended 51 public meetings throughout the course of the project.

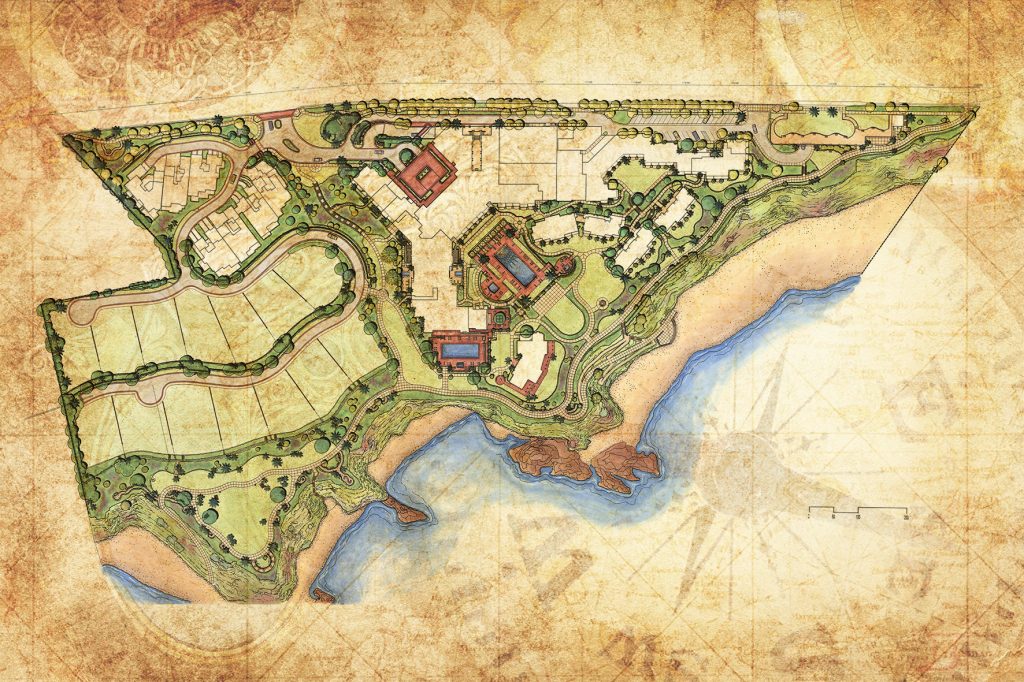

From the outset, the aim of the development and design teams was to create an open area that evoked a strong sense of place. The planning process involved evaluating the views, the best beach access points and the relationships between public and resort spaces, plus the city’s handful of requirements related to handicapped access, restrooms, parking, picnic tables and seating. “In parallel, we were trying to figure out how we would distill everything that expressed who Lagunans perceived themselves to be … so it would be reflective of them and be a place they could emotionally connect with,” William adds.

From the outset, the aim of the development and design teams was to create an open area that evoked a strong sense of place. The planning process involved evaluating the views, the best beach access points and the relationships between public and resort spaces, plus the city’s handful of requirements related to handicapped access, restrooms, parking, picnic tables and seating. “In parallel, we were trying to figure out how we would distill everything that expressed who Lagunans perceived themselves to be … so it would be reflective of them and be a place they could emotionally connect with,” William adds.

Inspired by nearby Heisler Park, Treasure Island’s curvaceous path gradually unfurls to reveal an ever-changing technicolored landscape with myriad viewing points and alcoves for sitting.

“The views from the park vary, and the coastline becomes more exposed the farther out toward the bluff you get. As a result of the dramatic topography across the site, the park isn’t visible from the road, so it feels like you’re personally involved with the space,” William explains. “The strongest reaction we heard was how much people liked the bluff-top promenade. This was an exercise in combining a lot of colors and textures, and seasonality through the plant material.”

His team also was inspired by a series of coastal California plein-air paintings, historical books on California and the robust Mediterranean plant palette. Historically, the site encompassed seven separate plant communities; oaks and sycamores were planted at a higher elevation while naturalized, salt-tolerant and bluff-native plants informed the coastal landscape as it approached the surf. Today, sea lavender, orange cape honeysuckle and orchid rockroses grow alongside spindly century plants, spiky agave and velvety Mexican sage. “We wanted to create a wide range of experiences for people because they’re going to stay a while,” he says of the variation. “If it’s the same over and over again, it’s not very interesting.”

Aside from PCH’s eucalyptus plantings, which William’s team rehabilitated from disease, approximately 300 trees and palms from the former site were inventoried, either boxed or heeled-in and stored, and transported to off-site nurseries before being replanted. “As well as getting instant maturity, we were able to bring back some of that history that had grown with the community of Laguna,” he says. Also in keeping with history, two palm trees named after Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, who filmed the 1954 film “The Long, Long Trailer” at Treasure Island, continue to sway just outside Montage Laguna Beach’s Studio restaurant.

Community Asset

It’s impossible to discuss Treasure Island Park without mentioning Montage Hotels & Resorts, which debuted Montage Laguna Beach in February 2003. “When CEO Alan Fuerstman walked into the lobby and saw the beauty of the space, he knew this was an opportunity to create something special,” says Todd Orlich, the sprawling resort’s general manager.

The flagship property encompasses 30 acres including a 250-room hotel, 28 residences and 14 acres of common space composed of dining areas, a 20,000-square-foot spa, more than 7 acres of manicured parkland and gorgeous beaches.

While Montage deeded the park and beaches to the city, effectively giving the public access to the land, it maintains the grounds in perpetuity. A crew of up to 12 gardeners cares for the park, and a recent Hearts of Montage beach cleanup drew roughly 100 volunteers from the resort and the local community.

“Our relationship with the community has gotten stronger and stronger, and the park has always been a big part of it,” Todd says. “This is [people’s] gathering spot for a birthday, a sunset ritual, an afternoon stroll, photography or plein-air art painting. People really love this beautiful slice of heaven.” To that end, the resort is conscious of playing an active role in the community. During the holiday season, for instance, it opens the ocean-facing Pacific Lawn and resort premises for its annual tree lighting ceremony. The turnout has increased from 1,800 locals in the event’s inaugural year to upward of 4,000 in 2013.

“The park was designed in accordance with California Coastal Commission requirements to be a passive pedestrian experience, so you don’t have bicyclists and skateboarders,” adds Christine Loidolt, business center manager at Montage  Laguna Beach. “People are comfortable walking their dogs, strolling with their kids and not having to worry about anything except looking at the ocean.”

Laguna Beach. “People are comfortable walking their dogs, strolling with their kids and not having to worry about anything except looking at the ocean.”

For these locals, the park’s verdant lawns function as an extended backyard. Alongside picnickers and sun-worshippers, registered yoga instructor Carl Brown hosts free Yoga in the Park classes, passing any donations on to charities like the Himalayan Children’s Fund. Each October, meanwhile, the annual Laguna Beach Plein Air Painting Invitational kicks off its weeklong festivities with a two-hour paint out inspired by the park’s striking vistas of coves, rock formations, sun and surf.

Along the promenade, the park provides four beach access points, and a tide pool docent program educates kids and adults alike about the communities of sea stars, sea snails and mussels that live in a “no-take zone.”

At the southern end of the park, the grassed-over rooftop of the public parking structure offers fully accessible oceanfront views. Furthermore, Christine explains that Treasure Island Park features the only beach ramp in all of Laguna that was built in accordance with the Americans With Disabilities Act’s Standards for Accessible Design.

Given the melange of voices that influenced its construction and the years of planning it took to see that construction through, Treasure Island Park was warmly welcomed upon its unveiling. “It was an amazing working relationship between the city manager and the developer,” William says of the one-time opportunity, considered the largest project of its kind in the community’s history. “The public process was contentious at times, with lots of opinions, but at the end of the day, good design came from that process. As these things go, it could’ve been whittled down to the lowest common denominator. Instead, it ended up being a significant win for the community and a good private endeavor.”

Driving along PCH, with its sweeping views of an azure ocean, and realizing that there’s a quiet place—a community space—where people can stop, sit and rest their eyes upon the horizon is treasured knowledge in itself.