A Laguna Beach landscape architect is painting the town green with vertical gardens that beautify, enchant and, most of all, show that art comes in many different forms.

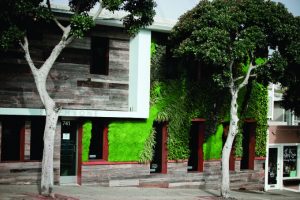

Laguna Beach is a mecca for some of the country’s finest artists—every summer there is, of course, the renowned Festival of Arts, showcasing paintings, sculptures, photography and more; Pageant of the Masters, a world-famous living pictures show; Sawdust Art Festival, exhibiting handcrafted items from local artists; Laguna Art-A-Fair, with U.S. and international exhibitors; and a slew of year-round galleries, to boot. Yet, plants as a medium for magnificent artwork don’t immediately come to mind. But passersby who have seen the large “living wall,” or vertical garden, in the parking lot of Obagi Skin Health Institute on South Coast Highway might think differently. The piece is massive, requiring you to take several steps back to really evaluate its full impact. Playing with scale, form and swirls of purple and green, it is a beautiful and brilliantly executed living, growing work of art. This is just one masterpiece that can be seen around town from landscape architect Scott Hutcheon and his Laguna Beach-based firm, Seasons Natural Engineering, which is one of the nation’s top businesses that produce vertical gardens for commercial and residential spaces. As the living wall movement has boomed over the past decade due to the trend of incorporating eco-friendly and sustainable design, once-plain walls are given new life thanks to companies like Hutcheon’s. With the drought in mind, Hutcheon employs recirculating water systems, as well as drought-tolerant plants that not only lend themselves to sustainability but beauty, too.

From College to Hydroponics

Hutcheon graduated from California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, in 1998, with a bachelor’s degree in environmental design and landscape architecture. Inspired by the groundbreaking work of prominent French botanist Patrick Blanc, who is considered the inventor of the modern living wall, Hutcheon founded Seasons Natural Engineering in Laguna Beach in 2000. Around Laguna, the firm’s work can be seen at businesses like Obagi and the Seven4one hotel—where the verdant plants grow against a backdrop of gray-colored, reclaimed wood—as well as private residences. Beyond city limits, Seasons has designed living walls for the Edwards Lifesciences parking structure in Irvine, which, at 4,000 square feet, is one of the largest hydroponic living walls in North America; a green wall in the middle of South Coast Plaza; an outdoor patio wall at True Food Kitchen in Newport Beach; a succulent wall at the Little Owl Preschool in Long Beach; and many out-of-state projects. As successful as his firm has become, the landscape architect and engineer is always learning, searching for solutions and perfecting his green walls. One of the biggest challenges is irrigation. “Plastic module systems don’t get even water distribution,” Hutcheon says. “It’s not like plants that are growing in the ground, where moisture can spread more evenly. Due to this, Hutcheon instead opts for felt, which wicks water more efficiently and allows oxygen—used by the plant for respiration (turning sugar into energy)—to reach the root zone. Hutcheon explains that vertical systems covered with felt, which can be a substitute for soil, retain water for a longer time (picture wool when it’s wet) and hold plants more securely than units made of plastic or wood. Slits are cut into the felt, plants are inserted and then stapled to form pockets. At a time when rain has been scarce and conservation is important, Hutcheon employs systems that recirculate the water. At Obagi’s walls, for example, a trough collects any runoff, then diverts it to a tank for later irrigation to avoid waste. Before the felt method, Hutcheon worked with systems like GroVert, which he helped develop and launch for living wall company BrightGreen. Basically, the plastic units come in two sizes and can be stacked or grouped to create larger wall pieces. Each unit features cells (or compartments) that are lined with a moisture mat and can be “populated” with small plants bought from a nursery. Additional accessories include an irrigator, water collector tray and decorative wood frame. “They work well for smaller pieces, and we still use a few for smaller projects,” Hutcheon says. Seasons also has been employing hydroponic gardening, a method for growing plants using water rather than soil, into their wall systems with great success. For this technique, water and a nutrient solution are combined and can be easily controlled. “With hydroponics, you can really grow many more things that can survive and thrive than with soil,” Hutcheon explains. “You get more oxygen and nutrients going to the root zone. It literally pumps up the plant every day. With soil, there’s the potential for root rot and lots of diseases. Horticulturally, I think hydroponics is healthier for plants.”

Planting Smart

While the type of vertical gardening system is important, so are the shrubs that go in them. Hutcheon is always rethinking the plants he uses, looking out for stronger performers while taking away fussier, low-performing specimens. Ferns are among the plants used by Hutcheon; some of his favorite types, appreciated for their graceful textures and durability, are sword, lemon button, bird’s nest, kangaroo, jester’s crown and asparagus fern. Other preferred plants include coral bells (a type of perennial) due to their many colors and succulents like heartleaf ice plant and hens and chicks (also commonly called houseleeks). He must be on alert for changing conditions; a downy mildew that recently afflicted the red apple variety of Aptenia (a type of ice plant) in Southern California has forced Hutcheon to change out the stricken species with something else.

Of course, the drought is another factor to keep in mind. While many succulents use less water, some aren’t good choices for a living wall; Hutcheon says he has to steer clients away from varieties like the popular paddle plant, which tends to droop when grown vertically, and echeverias, which get “stalky.” The Sempervivum group of succulent plants, including hens and chicks, are more tight and compact and work much better in vertical walls. Other favorites include flax lilies, a native of Asian and South Pacific islands, and bulbine, a South African succulent with yellow or orange flowers; all of these plant options are drought tolerant, Hutcheon says. Working with a palette of plants and tools like the hydroponic method, the rest is artistry. And Hutcheon continues to seek inspiration, which often comes from simply walking through a nursery or looking at other vertical walls. “These days, I feel like everyone is probably getting ideas from everyone else,” Hutcheon says. “We’re always trying out new things. I’ll see something and think, ‘Hey, that might work in Laguna Beach’s climate.’ ”

Vertical Gardening at Home

With these tips, you’ll have a green thumb in no time.

While you might desire to build a grand living wall in your home akin to one of the pieces that can be seen at Obagi Skin Health Institute or Seven4one hotel, it’s a good idea to start small to see if vertical gardening is a good fit for your space and level of expertise. To start, determine where you want to locate your vertical garden. Think about the strength of the wall or fence, the type of plants and plant compatibility—meaning you should select plants that have similar water, shade and sun needs. Next, decide which type of system you want to use. There are several styles of living wall systems that are best used for vertical gardens, including: mat systems, which are made from felt, coir fiber or rock substrate; block systems, which are durable, structural units shaped like bricks or blocks; loose-medium systems, which include window boxes and wall containers, and are good for community gardens or homeowners who like to use soil for planting mediums; and homemade systems, which uses repurposed items like pallets, bookshelves and jars. For beginners, Scott Hutcheon, living wall expert and founder of landscape architecture firm Seasons Natural Engineering, recommends using a kit like GroVert, which he helped develop and is available at garden centers and on Amazon.com. He advises to start small and simple, using low-maintenance plants such as coral bells, jester’s crown or sword fern, and succulents like heartleaf ice plant and hens and chicks. But don’t get too hung up on using a certain kind of plant in your vertical display. “Some customers may insist on specific plants,” Hutcheon says. “I always find that they are ultimately going to be happier with a green wall that is growing and looks good than using a certain plant that is exotic, delicate and going to eventually die. It’s less of a headache to work with things that you know are going to look good.” ~ Written by Lisa Hallett Taylor