Laguna artist Andrew Myers constantly thinks up new ways to express his creativity. – By Lauren Simon

Andrew Myers is a jack-of-all-trades in the art world. Like a handyman who can fix anything, Andrew is skilled in bronze sculpture, bronze relief, drawing and painting. As the inventor of portraits made using drywall screws, he naturally wields a mean drill, too.

Andrew Myers is a jack-of-all-trades in the art world. Like a handyman who can fix anything, Andrew is skilled in bronze sculpture, bronze relief, drawing and painting. As the inventor of portraits made using drywall screws, he naturally wields a mean drill, too.

Around Laguna Beach, where he makes his home, Andrew first became known for his bronze sculpture in 2004 when his four-foot bronze woman called “The Shopper” was chosen by the city as a public art installation at Beach Street and Ocean Avenue.

Andrew gained public attention for his work again last year when the city chose one of his sculptures as a public art installation, this time for the base of Brooks Street. The new piece, called “The Classic,” features a surfer holding a bright orange longboard. The work was installed in May, but Andrew removed it several months later after the city asked him to do away with the sculpture’s orange paint and reorient the piece, which some people had complained obstructed ocean views.

Most recently, Andrew completed nine bronze relief panels for St. Catherine of Siena Parish here in Laguna depicting the life of the Italian nun in the 14th century. He also recently installed a commissioned bronze sculpture of four children climbing a 13-foot beanstalk in a private home in San Juan Capistrano. Andrew’s work is diverse and off the beaten trail, which is made obvious by his latest creations.

Screwball Artistry

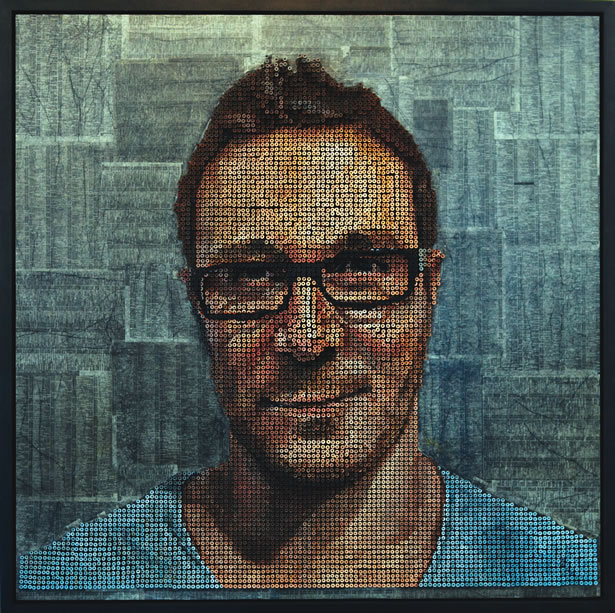

Bronze sculpture is not the only kind of Andrew’s artwork that is turning heads these days. He’s also known for inventing screw art—large portraits created in relief using thousands of drywall screws affixed to a board—which he later shows at the Festival of Arts.

Andrew came up with the idea for the screw portraits while working on the relief panels for a church. “I had had an idea years ago about using screws for a whole piece,” he explains. “It just hit me one day. I thought, I can make a grid and start putting screws in. I didn’t realize how much work it was going to be.”

The intensive work begins with drilling 10,000 holes in a 4-by-4 panel of ¾-inch plywood, which Andrew covers in paper from a telephone book. He then draws on the paper to create the outlines of the portrait or whatever object he plans to create in relief. After that, he affixes the 10,000 screws into the panel, carefully screwing each one in only as far as it needs to go to create a smooth contour when viewed from a distance. Once all the screws are in place, Andrew paints the top of each one to add color and depth to his subjects. In other words, his screw portraits are like pointillism in 3-D, with each screw almost touching the one beside it to create an image out of thousands of tiny raised dots.

Andrew is drawn to relief sculpture both in bronze and in screws (and, he says, maybe someday in other mediums, such as bolts) because of its complexity and the difficulty of doing it well. He explains, “Sculpture is real. It’s in front of you. It exists. It’s completely true, where painting is a complete illusion, a complete lie, where it’s implying actually something is there but it’s not.

“Relief sculpture is a bit of both,” he continues. “It’s the ultimate illusion because you’re creating something in 3-D that makes you believe that something is coming farther out than it really is. I think relief sculpture is one of the hardest forms of art that exists because you’re dealing with so much more than form. It’s all about perspective. How the shadows land on the screws is very important. In sculpture, the nose has to be out a certain length, but in relief, it has to be shorter, but you still have to get the illusion that it’s coming forward.”

Always Inventing

Using screws to create relief sculptures comes naturally to Andrew, who considers himself as much an inventor as an artist. “First and foremost, I’m an artist, but I feel like I’m trying to invent new things constantly,” he explains. “I saw some Michelangelo sculptures and some Bernini sculptures, and I realized I would never be that good. … Once the pressure of realizing that I don’t have to create the perfect figure was gone, my goal was to reinvent constant new forms of art or things I never saw before. I’m in the studio now, not trying to create the most beautiful piece of art, but I’m trying to come up with something that’s completely unique.”

Andrew was encouraged to be inventive from a very young age. He recalls tinkering in his father’s woodshop when he lived in Spain, where both of his parents worked as missionaries in the 1980s. “My dad had a woodshop, and he always let my brother and I go to the workshop and play around,” Andrew explains. “If we wanted something, my parents always encouraged us to make it ourselves. So we grew up making all kinds of things.”

Andrew moved to Seattle when he was a teen, but after finding himself “daydreaming a lot in school,” he took a job in construction rather than apply to college. Then one late summer day on a trip to Laguna Beach, he happened upon Laguna College of Art and Design (then called the Art Institute of Southern California).

“I always wanted to do something with art,” Andrew says of that day in 1999. “I don’t know why [but] I pulled over. I just wanted to check out the school. And the second I walked in there and saw people doing sculpture, I knew I wanted to do that.”

Andrew had no portfolio, but he diligently worked on some sketches that he brought back to the school. When the admissions officer saw his talent, he was accepted on the spot and enrolled that fall.

“It would not surprise me that Andy’s raw talent was noticed [by the admissions officer],” says his former sculpture instructor Marianne O’Barr. “I had Andy in my sculpture course his second year at LCAD, and he was very eager to absorb the instruction, and he did very well in this class. It has not surprised me the successes that he has had since he left LCAD.”

Making Ends Meet

Two years later, at age 22, Andrew graduated and began his artistic career. To make ends meet financially, he traded his work for food, a car and other essentials. When he was accepted into the Festival of Arts for the first time in 2002, he charged all his materials and foundry work on a credit card. “I cast all my pieces and then the first sale I made, I paid off the credit card,” he says.

Now 31, with a wife and a new baby, Andrew is no longer living so close to the edge, earning more than half of his income from commissions and selling his work in art galleries in San Francisco, San Diego and Lahaina. Locally, he promotes his work at the Festival of Arts and through word-of-mouth. He exhibited at the Diane Debilzan Gallery in Laguna for a few years, but ended that relationship in 2007.

Like many artists, Andrew says he finds showing his work in galleries to be “extremely frustrating,” because gallery owners typically take 50 percent of an artwork’s sale price. For Andrew—who says he pays up to $3,000 for material and casting each bronze piece—that means earning only $2,000 on a $10,000 sale.

“For me personally, it’s a huge issue,” he says. “I don’t dislike gallery owners; I think some of them are really awesome people. I just think the way the whole system is set up, as an artist, you put your blood, sweat and tears into a piece, and then you pay 30 percent of it to get it cast, and then the gallery takes 50 percent, and you walk away with 20 percent of everything you’ve done. It’s extremely frustrating.”

Family Matters

Despite his frustration with the economics of being an artist, Andrew seems happy with his artist-inventor lifestyle, especially these days since he and his wife, Christina, recently had their first child. Andrew stays home with baby Crosby every morning while his wife works as an environmental health specialist; when she returns home, he goes to his Laguna Canyon studio in the afternoons and evenings to work. In their now-rare free time, Andrew and Christina enjoy eating out at Laguna landmarks such as 230 Forest, Eva’s Caribbean Kitchen and Brussels Bistro. Andrew also likes to go backcountry camping with his brother in the Sequoia National Forest.

Regardless of where he is or what he is doing, Andrew says he is “always thinking about inventing the next thing” that will allow him to express himself, have fun and make money to support himself and his family. “The truth is my art is my hobby,” he says. “It’s my hobby. It’s my job. It’s my life. If I’m not doing it, I’m constantly thinking about it.”

But, he quickly adds, “Freedom to me is very important. I turned down a few contracts with big publishing companies because they wanted to hire me for 10 years, and that would mean tying me down to everything they wanted me to do. For me, I need to feel that I’m still in control of my life, even if I have less money. I want to have that time to be myself.” LBM