Laguna Beach resident DJ Roller has built a career on his fearlessness in extreme environments, his passion behind the camera’s lens and his dedication to sharing his experiences with the audience.

By Ted Reckas | Photos courtesy of DJ Roller

Fifteen-year-old DJ Roller was 273 miles away from his home in Atlanta, bouncing down a dirt road in Live Oak, Fla., in his buddy’s pickup truck. Dangled in the bed above several scuba tanks were six oxygen sensors that he acquired from a friend who worked in a hospital. They clanked with every bump in the road. “This weekend’s going to be awesome,” DJ thought as they drove in silence. The boys weren’t making home-brew nitrous oxide or doing extra credit for chemistry class. They were preparing to go scuba diving in underwater caves.

The tanks held trimix gas—a blend of oxygen, helium and nitrogen—which is less toxic than regular air on long, deep scuba dives. Trimix was hard to find in 1986, so DJ bought thick Navy diving manuals and did his homework to concoct his own. Miscalculations could spell death, so DJ checked and rechecked his handiwork before setting off on the bumpy road to rattle the tanks and mix the gas molecules.

DJ’s whole life has unfolded like this: making his own cave diving gear, pioneering the use of the first high-definition cameras underwater, filming groundbreaking expeditions with elite Navy dive teams, developing 3-D cameras with James Cameron.

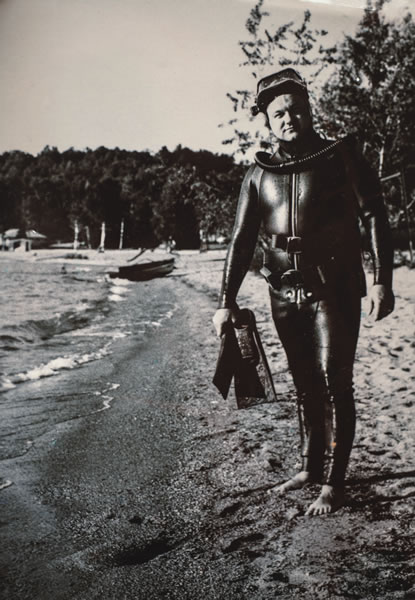

His grandfather, Bill Darling, was a self-taught diver and an early source of inspiration for DJ’s life of adventure and career of setting precedents. On a living room bookshelf in DJ’s home high in the Laguna hills sits a black-and-white photo taken in 1962 of Bill standing at the edge of Crystal Lake in Beulah, Mich. In the picture, he is holding an Aqua-Lung, the first generation of scuba gear invented by Jacques Cousteau, which he purchased at a hardware store. “Back then I think the rules of diving were 12 things printed on the back of the tank,” DJ comments.

As he acquired dive skills through his youth, DJ met some of the great pioneers of cave diving who lived in Atlanta, like Sheck Exley (a cave diver and widely-regarded author who died trying to set a depth record of 1,000 feet). DJ was mentored by Stan Waterman, a looming figure in early underwater filmmaking. “Someone said we should meet,” is all he says of how the relationship began. His simple descriptions are telling—DJ is as understated as they come. He appears incapable of panic, like he could see a tidal wave in the distance and calmly formulate a plan of action in the seconds before it hits—and execute it successfully.

Adventures in Film

It is unclear whether DJ’s demeanor is cause or effect of participating in some of the wildest experiences known to mankind. Regardless, his calm disposition has remained consistent, contributing to his many accomplishments.

After apprenticeships with underwater filmmakers like Stan Waterman and Armando Jenik, DJ went to work as a cameraman in the film and video unit at Turner Broadcasting System. Among his shoots at Turner were “Eco-challenge Morocco” (1998), a feature film in Iceland, and a documentary on anthrax labs in Kazakhstan. Since Turner was Sony’s largest customer in 1998, DJ experimented with their first professional-grade HD camera, the HDW-700A, and shot the first HD footage under the sea ice in Antarctica for the PBS show “Nature” (2003), which also appeared in BBC’s “Planet Earth” (2006). For this, he received the Antarctica Service Medal from the National Science Foundation.

Few people have such highly developed parallel skills of technical diving and cinematography, so when DJ produced a PBS NOVA special on the Naval recovery mission of the USS Monitor, “Lincoln’s Secret Weapon” (2000) the network couldn’t have asked for someone more qualified. The Monitor, constructed using iron with steam-powered propellers, was a futuristic ship in 1862. It sank in 250 feet of water off of Cape Hatteras, N.C., where volatile weather and currents lurk below the water’s surface. The effort to salvage the ship at this dangerous depth was as much a historic mission as it was a chance for the Navy to test the limits of its elite technical dive team, Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit Two. While the Navy divers were attached with support lines to the surface, DJ swam freely so he could film around them.

The shoot marked the start of a long relationship between DJ and the Navy. He created, produced and shot the National Geographic TV documentary “Super Sub” (2006) on the Navy’s most high-tech submarines. He later created and produced his own series for the History Channel, “Deep Sea Detectives,” and has since produced, directed and shot TV documentaries and IMAX films alike.

High-Definition 3-D

DJ was a close colleague of Vince Pace, who designed and built the underwater lighting systems for James Cameron’s films “The Abyss” and “Titanic.” Cameras that captured 3-D in HD didn’t exist in 2000, but DJ received a call from Vince saying James wanted to build one.

“I was on a plane the next day,” DJ says. “We were up till whatever time in the morning, hot-wiring these HD cameras together to see if we could synchronize them.”

Their experiments led to the camera system James used to make “Ghosts of the Abyss” in IMAX 3-D, a documentary about his expedition to the Titanic wreckage on the ocean floor, and the Emmy-winning “Expedition: Bismarck,” with DJ as a cinematographer on both.

DJ went on to develop the most advanced digital 3-D underwater housing in the world and even built a dive mask that allows him to see his footage in 3-D as he shoots it. The camera system has been used in “Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides,” films for Laguna Beach-based MacGillivray Freeman Films and numerous others.

Roller Legacy

Roller Legacy

Still, the filmmaker’s life is not without sacrifice. In 2007 he was about to leave for a month for South Africa to finish the IMAX film “Wild Ocean 3D.” As his ride to the airport arrived, his then 4-year-old daughter, Kennedy, walked out of her room with a backpack, holding the little green snorkel mask she used in their swimming pool.

“I’m ready to go,” she stated.

“This cute little girl in a mask … that’ll choke you up,” DJ says, recalling the episode. But soon enough, she would be allowed to join.

By the time DJ’s son, Jameson, was 3, he was doing dives in the bathtub with the smallest scuba regulator on the market and a backpack that held a tiny reserve tank built by DJ.

Jameson, now 12, and Kennedy, 11, plan to follow in dad’s footsteps. Jameson has worked as an assistant on DJ’s recently released 3-D IMAX film, “Great White Shark,” filming researchers as they tagged sharks off of the Southern California coast.

Kennedy joined her dad on a shark dive at Guadalupe Island for the same film. DJ reports she was unafraid as 18-foot great whites swam just outside the cage where she shot stills. “That was beyond my wildest dreams to take them on a project and have them contribute,” DJ adds. The entire family has credits on “Great White Shark”: DJ’s wife Melissa, formerly of TNT Television and Turner Classic Movies, was also line producer.

Coastal Inspiration

While the family was happy in Atlanta, DJ traveled to Southern California for work several times a year. This fueled fond memories of summers spent in the area during DJ’s childhood, making the family’s 2011 move to Laguna almost inevitable.

“Atlanta made it easy to jump to a lot of places, but you don’t have that connection to the ocean on a daily basis,” DJ explains. “We looked for the sense of community [Laguna has] here. We have neighbors who are sculptors and painters, and there are other film producers in town. The whole town is into the arts. If people ask what you do, you don’t get a blank stare, like, ‘What do you mean you go underwater and take pictures?’ ”

As much as he loves his adopted home, he has no plans to stop traveling and filming. For DJ, the ocean isn’t just a subject, and films aren’t just a product—his work is his way of being.

“Even though I do Hollywood movies and concerts with U2 and all that stuff—which is all fun—I continue to do this as well because I like exploring the ocean,” he says. “When you go to an IMAX theater and a little kid is pointing at an elephant or a shark, you know that it’s having a positive influence. If we can do that as filmmakers, that might help all of us understand the planet and maybe care about it a little bit more.”

His new film, “Great White Shark” (released internationally this year), is a paean to one of the most feared animals in the ocean. Featuring the first ever HD 3-D ultra slow-motion shots of great whites jumping, it is a celebration of their magnificence in movement. When discussing the film, DJ emphasizes its mission of recasting the animals as an important part of the ecosystem first; its cinematographic achievements come second.

DJ’s motivation is unique: to inspire the same wonder and appreciation he feels when in nature’s wildest places. “The ultimate would be for the audience to see and experience and sense the exact same thing you did when you were there, which is almost like the unattainable image. As we move through film … into digital and then 3-D, eventually it will be holograph and other methods,” he says.

“Some people fear change,” he says of the digital technology he has embraced. “Fear is good, but change is good, too. I’ve always been into new technology as a tool to push the creative side of what we do as filmmakers.”

While he aims for this goal, there will be no shortage of adventures. Recently he shot with a Space and Naval Warfare Dive Team, for which he had to attend aviation survival training. The instructors thought he was from the CIA since he was the only attendee not in uniform.

“I’m a filmmaker,” he said.

“Sure you are,” came the response. LBM