Over the last 50 years, the Pacific Marine Mammal Center has rescued thousands of pinnipeds, taken part in important research and educated countless schoolchildren.

By Sharon Stello

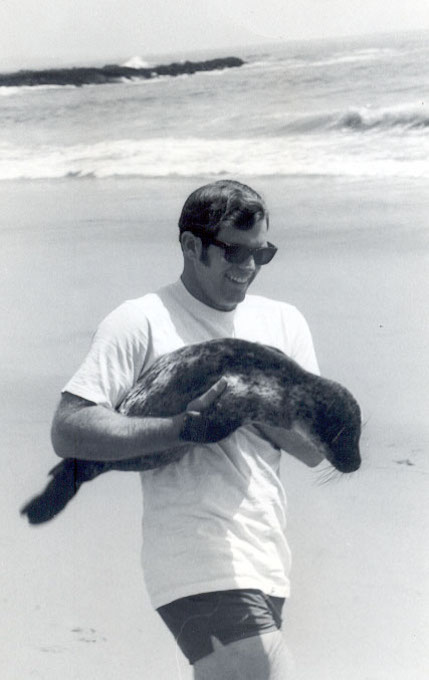

It all started five decades ago with a harbor seal, stranded on the shore in Newport Beach. A little girl told lifeguard Jim Stauffer about it, suggesting the animal might need help. Stauffer put the seal in his jeep, but it jumped out. It must be healthy and just needs rest, he thought. But concern for the creature led him to check back later—and it was still there.

He took the seal to Dover Shores Animal Hospital where a veterinarian, Dr. Rod La Shell, determined that the animal had lungworms. Following La Shell’s advice, Stauffer nursed the seal back to health before returning it to the ocean.

Inspired by that experience in spring of 1971, a grassroots group started Friends of the Sea Lion, which later became the Pacific Marine Mammal Center. Now based in Laguna Canyon, run by a few paid leaders and more than 200 volunteers, the organization has expanded over the years to focus on education and research in addition to treating stranded and injured pinnipeds. The nonprofit was the first licensed marine mammal rescue and rehabilitation center in the state—even predating the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972—but is now part of a network with six other centers along California’s coast.

The PMMC has rescued more than 10,000 animals, hosts up to 50,000 visitors each year and educates 10s of thousands of students annually. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the center has pivoted to provide education virtually, now reaching kids around the world. Programs are also offered at children’s hospitals through a partnership with the Ryan Seacrest Foundation.

This year, the center celebrates its 50th anniversary, with plans for a special gala on Nov. 7 at the Festival of Arts grounds. It has also launched a webpage dedicated to the milestone with a timeline and an area for community members to share favorite memories about PMMC. Limited edition products and apparel are also for sale through the gift shop online in honor of this golden anniversary and to support the center’s work.

While technology and medical treatments may have advanced over the last five decades, PMMC CEO Peter Chang says, “the heart and soul of this place has never changed.”

Chang believes the center’s efforts are important because they help to right a situation caused by people. Animals are found with gunshot wounds, hit by boats or entangled in fishing equipment, and they are affected by fertilizers washing into the sea, leading to harmful algae blooms that produce seizure-causing neurotoxins. The animals are also affected by climate change—seals and sea lions need to go further and deeper to find cold water fish, leaving pups behind for longer, which can lead them to starve or strand on the beach.

“Almost every reason is because of human interaction. We feel, as an organization, as a team, that it’s our responsibility to help these animals,” Chang says. “And the other reason is that these animals are such important parts to the ocean ecosystem. They’re not only prey for larger apex predators, but they also eat the smaller organisms, so they’re part of how things work in the ocean waters.

“If something happens to the pinnipeds or the dolphins or the whales—those are all marine mammals that we take care of—it will have a dramatic and devastating domino effect … and it will ultimately reverberate up to us as humans.”

On a Mission

The center’s humble beginnings are thanks to a handful of caring individuals. Stauffer established the group with fellow summer lifeguard John Cunningham, who was also a longtime science teacher at Laguna Beach High School, and a local veterinarian, Dr. Rose Ekeberg.

While Stauffer eventually moved to Northern California, Cunningham has remained involved until recently due to health issues. His wife, Stephanie Cunningham, recalls the group’s early years: Stauffer called a meeting at Main Beach for anyone interested in caring for sick and injured marine mammals since there was no such facility between SeaWorld in San Diego and Marineland of the Pacific (now closed) on the Palos Verdes Peninsula at the time. Of course, the organization didn’t have the canyon barn back then, so the founders had to improvise.

“Originally, Jim had his little marine mammal center at his home in Costa Mesa,” Stephanie says. “He had a big backyard with a couple of kiddie pools. And he would get volunteers. I was a volunteer and some of my friends were. We’d go down to Newport and pick up a couple boxes of herring and take it up to Costa Mesa and feed the animals.

“One time, my friend Judy Jameson and I went up with our box of fish and the little sea lions were all gone. There were supposed to be three or four of them and there was nobody in the yard. So we’re walking around in the residential area of Costa Mesa saying, ‘Has anybody seen any sea lions?’ ” she recalls, laughing. “… Then Jim moved to Laguna Beach. He lived up at Top of the World and he had a Jacuzzi, which became the second [location].”

Stephanie says one of John’s favorite memories was picking up a sea lion from the harbor department in Newport Beach. “It was sitting in the sink in their bathroom in the water and looking at himself in the mirror,” Stephanie says. “And John said, ‘They don’t really have to be wet, you know.’ ” He brought the sea lion home to get a fishing hook out of its mouth, driving down Coast Highway with the animal lying across the bench seat of his brown pickup truck, leaning its head against his shoulder. What he would later realize was the animal’s mouth wasn’t stuck shut, as he’d been told, and it could have bit him at any time.

Learning as they went, the organization’s crew remained committed to the cause. “Everything was all volunteer at that time,” Stephanie says. “There were no paid employees. Everything was just out of the goodness of everybody’s heart.”

Eventually, once the city assumed operation of the animal shelter, it allowed the PMMC to start using the barn on the property in 1976. John’s marine biology students built the original ponds at the barn, where animal operations are on the bottom floor. For many years, the upper level was used by the city for storage, but later was turned into the PMMC’s offices with an education area. Even so, the quarters are tight.

“Our treatment lab’s tiny. And, literally, they’re doing procedures in any open space they can find,” Chang says. “We’ve had to remove an eyeball this year, we’ve had to get rocks out of the stomachs of animals, get hooks out, all these different procedures. And to do them in hallways and just random open spaces, it’s not only unsafe for the animals, but it’s unsafe for the team that’s doing the procedures. So we need to really update ourself and be kind of the next-generation animal hospital that we need to be.”

In fact, a campaign is underway—with a portion of money already raised—to fund a $7.5 million expansion on the site; the project is going through the city’s permitting process. Eventually, Chang says, it’s possible the PMMC may open satellite locations elsewhere, but its hub will always be in Laguna Canyon.

Caring for the Animals

No matter how large or small the space, animal care is at the core of the center’s work. No one embodies that mission more than Michele Hunter, affectionately nicknamed the “marine mammal mama.” Hunter, who has helped at the center for more than 30 years, started as a weekend volunteer and is now director of animal care, working closely with Dr. Alissa Deming, the on-site veterinarian who also conducts research.

Hunter came to check out the center in the late 1980s and soon began filling her time with PMMC shifts in between her regular job at Taco Bell’s corporate office. The people are a big part of why she has stayed so long. “Back then and even now, it’s almost like a family here,” Hunter says.

Of course, the animals also hold a special place in her heart. Most are released back to the ocean after being treated, but some are deemed unreleasable because they won’t be able to survive in the wild.

“We’ve had to place animals in a permanent facility sometimes, whether they’re newborns or they’re blind or some other kinds of disabilities,” Hunter says, recalling one year when three newborn sea lions, Pearl, Xander and Gilligan, were given to a zoo while they were still taking bottles. “Pearl was just so special. These animals come in and they don’t have their moms so they bond with humans, which is what we don’t [try to] do, but … it’s a real honor to have a sea lion that thinks you’re its mom.

“We transferred them to the Oklahoma City Zoo and went and stayed there for a few days to teach them [how to care for these animals] and I went back like five years later and she still remembered me. I was like, ‘Oh my God.’ I was crying. … And she’s had a couple pups since then. They sent me pictures and did a whole little scrapbook for me and said, ‘You’re a grandma.’ ”

Most animals stay at the center for about three months while being treated and regaining weight. Over the years, Hunter has learned on the job how to draw blood, develop patient meal plans and do tube feedings. “I find that really exciting to keep growing and learning in this field,” she says.

Eventually, the seals and sea lions are fed whole fish, but they start on fish gruel, a kind of smoothie blend of ground-up capelin, Pedialyte and Nutri-Cal (a high-calorie supplement for dogs and cats). “And then we start adding herring, because it’s called the Burger King of fish. It’s got lots of calories,” Hunter says.

“… And we try to weigh animals weekly or every couple weeks,” she notes, “just to make sure someone’s not pigging out in the pool and taking all the fish.” The center staff and volunteers monitor each animal’s progress until they are deemed ready to return to the ocean.

Stephanie and John Cunningham attended almost every animal release before the pandemic hit. These typically take place early in the morning at Aliso Beach, which is not far from their home.

“You see them come in emaciated or injured and then they fatten them up … and you see these plump little sea lions [at the release],” Stephanie says. “… Sometimes they don’t want to get out of their cage. … One will poke its head out and then another one will and then one might start—and sometimes they go back. … And when they get to the ocean, so many times they bump their noses together and go off together and everybody cries.”

A Broader Impact

These days, the center is looking beyond helping individual animals to become even more involved in educational outreach as well as scientific studies. “Education allows us to mold the next generation of conservationists, marine scientists [and] biologists,” Chang says. “Those are the folks that are going to help solve these issues that are happening in the ocean waters and with these marine mammals.

“… A lot of people know us as this little red barn in the canyon and, you know, that’s something that we don’t want to go away. That’s this charm that we have—the kind of grassroots nature of this place. That’s never going to go away, but what we want to do is really leverage our core operations at the barn downstairs … with our education and scientific research to do bigger things, because we know we have this opportunity to do so.”

Deming, the center’s vice president of conservation medicine and science, was given a faculty appointment earlier this year at her alma mater, the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine, which is one of only two schools in the world with a formal aquatic animal health program. In this role, she gives lectures for the students—virtually, due to the ongoing pandemic. “We actually bring them on tours downstairs, we let them see procedures, we have them livestream into our necropsies,” Deming says. “Especially in Florida, where they don’t have seals or sea lions, these kids get so excited about it.”

And, as part of this collaboration, at least one vet student per year will shadow Deming for a month. This summer, a first-year vet student from the university will come to the center as part of her research project to help reconfigure bloodwork machines to provide more accurate results for marine mammals.

PMMC also partners with other researchers, maintaining a freezer full of tissue samples—taken during necropsies of marine mammals that have died at the center—that are given to scientists to help with their studies.

The center has started collaborating on research projects in other ways as well. In December, the PMMC received a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to develop a hands-off way to assess the health of the declining number of Southern resident killer whales in the Pacific Northwest. The idea is to use drones to catch samples of their breath, which can be analyzed in a lab. PMMC staff will work with orcas and the staff at SeaWorld San Diego to test out their methods before heading up north to join a research vessel out in the field.

In addition to her work as a vet treating animals at the center, Deming’s primary research focus is studying sea lion cancer as well as doing clinical research to find ways to “provide better care for our patients.”

She also examines “how we can utilize them to kind of understand what’s going on out in the environment, because they’re little sponges of the sea. They soak up all the contaminants or the toxins that are out there and then we can test them … to have some insight into what’s going on,” she says.

“… We can only take care of these animals while they’re in the hospital, but then we have to return them to the wild,” Deming adds. “And if we don’t fix and pay attention to the things that are going on in the wild, then they’re just going to show back up in our hospital.”

Studying marine mammals may also improve human health. For example, seals and sea lions swimming around appear to be a better indicator of when an algae bloom is releasing domoic acid than a boat crew taking water samples one location at a time. If a lot of animals are coming in with seizures, the center can sound the alarm so fisheries close sooner to prevent this neurotoxin from getting into the seafood we consume.

Marine mammals serve as kind of a “looking glass into the environment,” Deming says. “That’s why you have to ask questions about why these animals are showing up on the beach.”

For example, one in four adult sea lions coming to the center has cancer. Research determined that the cancer was caused by the herpes virus, but triggered by contaminants including DDT, which was dumped decades ago near Catalina Island and off the coast of LA by a company producing the pesticide. “Although people tend to have a short memory for environmental disasters like that, the effects of that … [are] still impacting not just sea lions, but marine life in general,” Deming says.

“… We now are using these animals to study virally-induced cancers in all species, because they all use the same mechanisms,” Deming says. “… Over 20% of cancers in humans are associated with infectious agents. And that’s the low-hanging fruit, to be able to stop cancer. If you can identify those infections or identify the way to stop that process, that triggering of the cancer, that can cure 20% of cancers.”

While PMMC staff members are doing remarkable things every day, from saving animal lives to making breakthroughs in research, Chang says he is most proud of his team’s ability to adapt through the years.

“The needs have changed over time. And our patients have changed over time,” he says. “… Previously, all of our patients were literally just starving. We’re now seeing a lot of patients with emerging infectious diseases and cancer and other things that we didn’t see before.

“And what this team does is constantly adapt. And the current chapter that we’re in, of trying to expand our impact with our emphasis on education and science, is just another area where they’re adapting. And they’re not only adapting, they’re embracing. And so I feel very lucky to be able to work with this team that just constantly wants to do the right thing.”