Hobie Surf Shop’s Gary Larson reveals how his passion for riding waves led to a long-lasting career crafting boards.

By Ashley Ryan

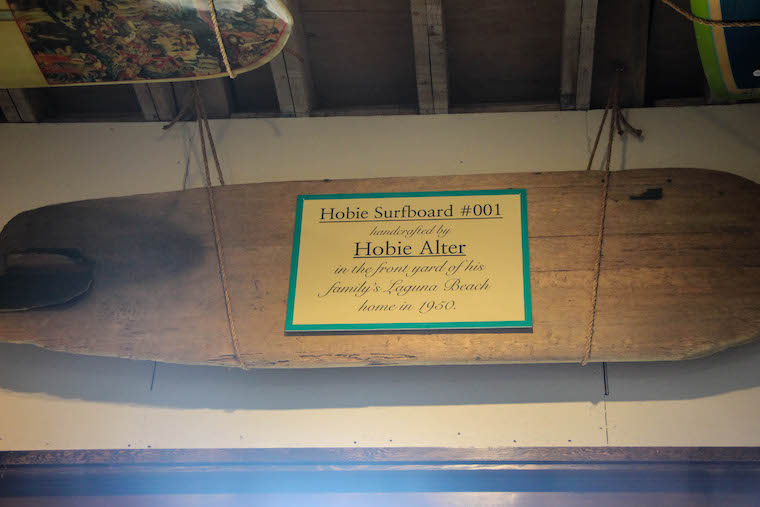

It’s been 70 years now since Hobie Alter carved his first surfboard, a simple wooden plank that was crafted in the garage of his parents’ Laguna Beach summer house. That was the start of a business venture that would grow to become one of California’s earliest surf shops—one that is still very much alive today.

Following the company’s milestone anniversary in 2020, demand for surfboards in Orange County is higher than ever, with more and more people swapping indoor activities for time at the beach due to COVID-19. But these modern boards look quite a bit different than Alter’s old-school wooden one, which is also, in large part, thanks to the founder himself.

In the late 1950s, Alter and Gordon “Grubby” Clark took to Laguna Canyon, where the pair experimented with polyurethane foam to create what many believe to be the first foam core surfboard. (A few years later, Clark went on to launch Clark Foam, which manufactured surfboard blanks, also in Laguna Canyon.)

While technology has taken the shaping world into new territory in recent years, shapers at Hobie Surf Shop still rely primarily on polyurethane foam for their specialty boards. Alter’s first shop (which he opened in nearby Dana Point with the help of his father, who grew tired of the balsa wood shavings that littered the garage) is now the home of surfboard shaper and designer Gary Larson, a Dana Point native who has dedicated much of his life to the industry. While Larson’s boards—each featuring his signature on the back—are available in Hobie’s retail locations, including Laguna Beach, he works from an on-site shaping room in the Dana Point store. He creates exclusively for Hobie in an effort to further instill the importance of both the culture and the artistry of handcrafted surfboards.

Surf Stories

Growing up in Dana Point, with world-class surf spots all along the region’s coastline, it’s not hard to understand why Larson fell in love with the sport. But while many surfers stick to the waves, he wandered into a surf shop and never looked back.

At just 14 years old, Larson began working for shaper Steve Boehne, one of the founders of the family-owned Infinity Surfboards, located just down the street from Hobie in Dana Point. “They really introduced me to shaping surfboards,” he notes.

Although he got this introduction at a young age, Larson did not start out on the production side. Instead, he was tasked with sweeping up the shapers’ shavings. “Because you actually walk in circles around the board [while shaping], you make this track and it would be about knee-high, all sides of you just shavings,” Larson says. “Shaving rooms are a little different now. Much, much cleaner than it was.”

In 1997, he officially started shaping for Infinity, where he would work for nearly nine years. “I owe everything to [Steve and Barrie Boehne] … for giving me that opportunity,” Larson says. “Steve is just an incredible teacher, and the patience that he had to have to get me through learning how to shape was crazy. … But I’m glad I stuck with it.”

Then, in 2005, Larson was asked to work for Hobie, alongside legendary local shaper Terry Martin. “I really jumped on that opportunity,” he adds. “… His approach and technique and his spirit about shaping was something I looked up to, [so] I was really excited to come work alongside Terry.”

Larson was able to work with Martin for seven years before he passed away, gaining an education in more than just shaping. “He was a really, really outstanding mentor,” he says. “I definitely learned a lot from him—just about life in general.”

In addition to his shaping skills, Larson is an expert in geography, having earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the subject from California State University, Fullerton. When he’s not at Hobie or in the water, he can often be found at Saddleback College in Mission Viejo, where he is a geography instructor.

Tubular Technique

Larson’s shaping room is situated on the side of Dana Point’s Hobie shop, attached to the main building but with its own separate entrance from the parking lot. Stepping inside, you’d likely be surprised by the darkness of the room, the vertical blinds over the high windows squeezed shut. The most important light source is placed not on the ceiling, but along the walls on the sides of the room, with harsh fluorescents casting deep, dark shadows across the surfboard blanks on the table in the center.

“To shape, I just use shadow,” Larson explains. “… You’re using your lights to be able to see all of the high spots, to see all of the shadows. We depend on it being extremely dark to see all of this. Lighting is extremely important.”

His tools are unique to him, something he says is true for nearly every surfboard shaper. Instead of using set instruments, shapers often invent their own, usually by reconfiguring woodworking tools or even items that can be found in the kitchen. Aside from standard sanding blocks, some of Larson’s tools include a Japanese saw, a grater often used for zesting when cooking, a tree trimming saw with the teeth filed into a straight line and an electric planer attached to a vacuum.

His process starts with a template, of which he has many. Some he created himself over the years, some belong to Hobie and others were gifted to him by other shapers. He uses this atop the polyurethane blanks to draw the outline of the board’s shape, then uses the modified tree trimming saw to get it to the right thickness. Larson then uses the planer to create the rough shape of the board, and sands it by hand until it’s finished. On average, he says, he completes 10 to 15 boards each week, spending less than two hours on each one.

“I get to go into my shaping room, close the door, put headphones on and not have to deal with anything but shaping a surfboard, which is really fun,” Larson says. “It’s pretty nice being able to sit down and be creative for the entire day.”

In addition to the shape of the board itself, Larson uses a refashioned block plane to strip down the wooden stringers that help give the board strength. Placed with either one in the middle, two closer to the sides, or all three, Larson’s stringers are typically made from redwood, cedar, basswood or even balsa, the same wood Alter used for his original board. He also adds fins made of wood, plastic or fiberglass.

When first talking with customers, Larson asks where they plan to surf. “Most shapers are really familiar with the waves and the beaches in their area,” he explains. “… The shaper understands the different rockers that are needed for a board for a certain type of wave. Like at Doheny [State Beach] and San Onofre [State Beach], those are two longboard-type waves where they’re a bit slower, generally smaller, than other beaches. … I’ve been fortunate to be able to travel to a lot of cool places so I have some general knowledge of what waves are like in different parts of the world.”

He compares the practice of making his boards to sculpting. “I have an image of the board in my mind and, then, use my hands to get to that point.” While he originally sketched the rails of a board when first starting out, he said now he relies solely on his skill, only measuring the width of the center, nose and tail along the way.

Since the local coastline doesn’t have very many beaches that are ideal for longboard surfing, Larson says Lagunans often buy his boards to surf at Doheny or San Onofre. “Many of the residents order their boards through the Laguna Hobie store and end up coming to my shaping room to talk about the shape of their board,” he adds.

And while he loves using his own boards, he says the most fulfilling part of what he does is when others love his work as well. “I love surfing, so, at the very least, I get to have fun on the things I make,” Larson says. “[But] having someone come and say, ‘This is the best board I’ve ever ridden’ makes me happy.”

Riding the Wave

While his job usually offers him a chance to relax and tap into his creativity, Larson says that the last year has been challenging because of a dramatic increase in sales. “Demand for surfboards has gone up and I can’t shape any faster. It’s nothing I’ve ever had to really deal with in shaping before,” he explains.

But even with the production challenges he’s had to face lately, Larson sees the positives in increased interest as well. “People aren’t traveling out anymore and people aren’t going to the gym so the beach is a great option,” he notes. “And it’s good because, now that people are more exposed to the beach, maybe we’ll take better care of these great places that we have access to.”

For enthusiasts in the area that are looking to be a regular footed surfer—or riding waves with your left foot forward, rather than goofy footed with your right—Larson recommends Upper and Lower Trestles, as well as Church, all at San Onofre, plus Salt Creek Beach. Internationally, he says that Jeffreys Bay in South Africa is one of his favorites. “That wave is incredible,” he notes. “… It’s a very long, right wave, and you can surf … for a few hundred yards, and your legs are burning at the end of it. [Plus,] there’s the fear of sharks.”

But, no matter where you surf, he says that handcrafted surfboards are an important piece of the sport’s heritage. “What we see in the surf culture today is a representation of the hard work that these surfers and shapers before us did to make it what it is,” he says, citing greats like Terry Martin and Timmy Patterson. “… So many new surfers grab a board from Costco and surf and are now a part of the surf culture, but don’t understand that their board just came from China.”

This is happening more and more, with the increased use of computer numerical control, or CNC, machines and computer-aided design, or CAD, files to manufacture boards over the last 20 years. Although it is quicker, and Hobie has begun to supplement some of its inventory with these boards during the busy pandemic, Larson says that, within the surf community, there is no desire to permanently move toward mass-produced boards. “Hand shapers take pride in being about to do it from start to finish,” he explains. “… We, [here at Hobie,] generally keep everything hand shaped and, even though we can’t do high volume, I think we’re continuing the legacy and tradition of how surfboards are made.”

A picture in his shaping room further confirms his ideals that the legacy of surfing lies in the ways of the past: He is pictured with Martin, a nod to his own personal history as well as an ode to those who have made local surf culture what it is today.